In a groundbreaking study, researchers from Columbia and Rutgers universities reveal that microplastics are even more prevalent in bottled water than previously estimated. The average liter of bottled water, commonly consumed around the world, contains nearly a quarter of a million nanoplastic fragments, challenging our understanding of plastic infiltration into our daily lives. As concerns rise about the potential health risks associated with microplastic exposure, the study opens a new chapter in the quest to mitigate the omnipresence of these tiny particles.

Table of Contents

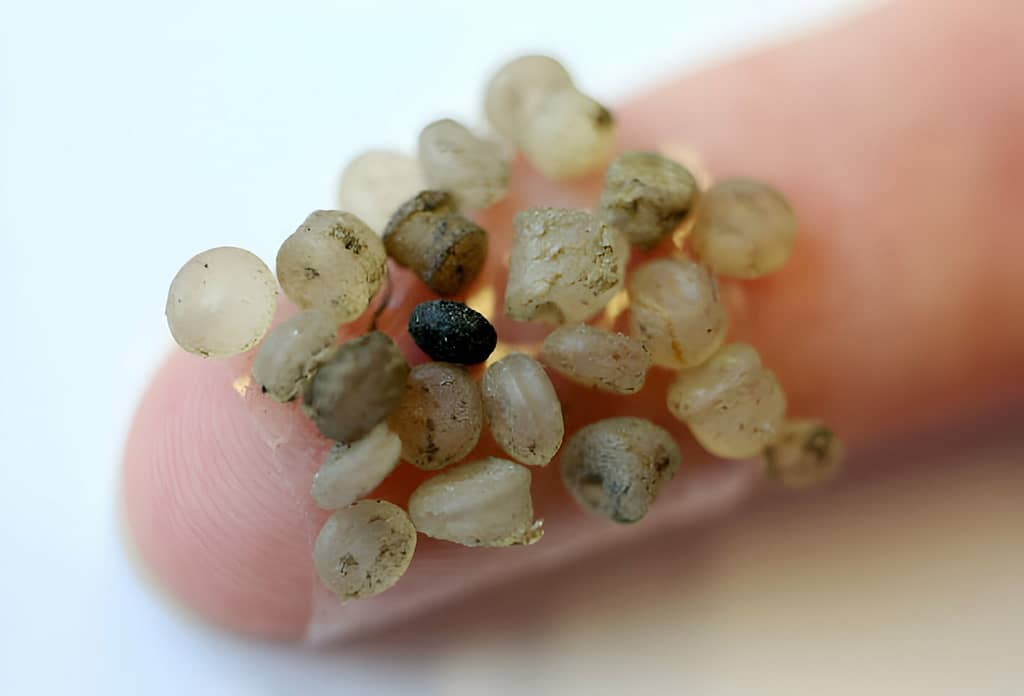

Unveiling the Invisible: Microplastics Across the Planet

Microplastics, minute particles of anthropogenic material, have been discovered in every corner of the globe. From Antarctic sea ice to the deepest ocean trenches, and even in drinking water, these tiny plastic fragments infiltrate diverse environments. The recent study sheds light on the alarming concentration of microplastics in bottled water, uncovering levels up to 100 times higher than previous estimates. Researchers analyzed samples from three common bottled water brands, revealing nanoplastic levels ranging from 110,000 to 400,000 per liter, with an average of approximately 240,000. The source of much of this plastic appears to be the bottles themselves, raising concerns about potential health risks.

The Broader Scope: Microplastics in Our Food

Microplastics extend beyond water sources and make their way into our food supply. Agricultural lands, treated with sewage sludge containing microplastics, raise concerns about contamination. European farmland, according to a study from Cardiff University, sees an annual contamination of 86 trillion to 710 trillion microplastic particles. This contamination reaches consumers unknowingly, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive approach to address the broader issue.

The Biodegradable Dilemma

In response to the backlash against single-use plastics, some companies have turned to biodegradable alternatives. However, research indicates that these alternatives might exacerbate the microplastic problem. Biodegradable products labeled as such can take years to disintegrate, often breaking down into smaller pieces rather than fully decomposing. The unintended consequences of biodegradable plastics underscore the complexity of finding sustainable solutions.

Glass Bottles: A Viable Alternative?

Switching to glass bottles could potentially reduce exposure to microplastics, as tap water generally has lower levels than water from plastic bottles. However, this transition raises environmental concerns, as the production of glass has a higher environmental footprint than plastic and other packaging materials. Striking a balance between reducing microplastic exposure and minimizing environmental impact remains a challenge.

Searching for Solutions: A Glimmer of Hope

Researchers are actively exploring various approaches to address the plastic pollution crisis. Efforts include leveraging fungi and bacteria that feed on plastic, developing water filtration techniques, and employing chemical treatments to remove microplastics. While challenges persist, these initiatives offer hope for mitigating the environmental and health impacts associated with microplastics.

Unknown Health Risks: A Call for Research

Despite the widespread presence of microplastics, the scientific community is still grappling with understanding their potential health risks. The World Health Organization’s 2019 and 2020 reviews emphasized the need for more research to determine the impact of microplastics on human health. The smallest nanoplastic fragments, measuring less than 10 micrometers, are of particular concern. As researchers delve deeper into the effects of microplastics, the importance of reducing plastic pollution remains a global imperative.

In the face of this pervasive challenge, individuals can make a difference by opting for reusable bottles instead of single-use plastics. As researchers continue to unravel the complexities of microplastics, a collective effort is needed to address the root causes and find sustainable solutions. The journey to reduce microplastic exposure requires a multifaceted approach, combining scientific innovation, environmental stewardship, and individual choices for a healthier, plastic-conscious future.